by Ted Williams

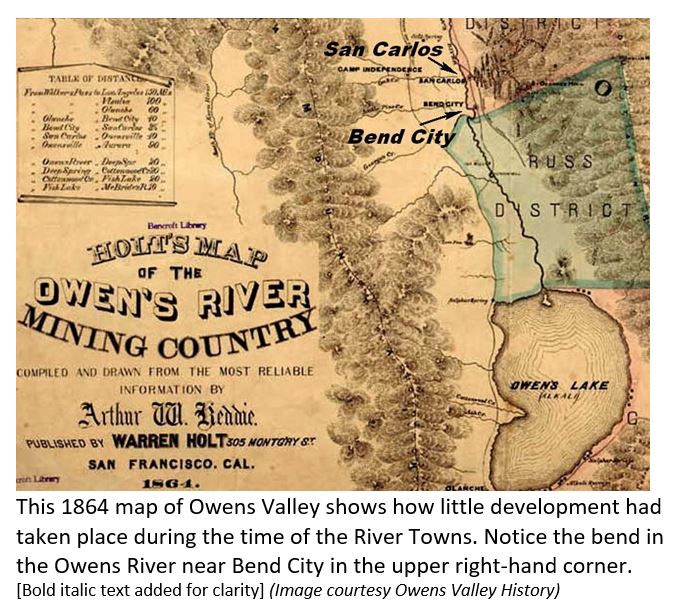

Before Inyo County existed there were towns along the Owens River populated by miners castoff from the declining California 49er Gold Rush. They were drawn to the Owens Valley River Valley, as it was called back then, by reports of riches coming from its eastern mountains. In the early 1860s miners, followed by merchants, coalesced into bustling communities along the eastern edge of the Owens River: Owensville, San Carlos, and Bend City. There was no local government, no infrastructure, a couple of roads, and initially few if any services.

These river towns were iconic mining communities that lived hard and died young. Many towns rose and fell so quickly they left little trace in the sand, or the pages in history.

All three River Towns began their lives in the early 1860s on the east banks of the Owens River. Bend City and San Carlos sprung up about 5 miles east of present day Independence. To the north, Owensville was established three miles northeast of Bishop, near the present-day Laws Museum.

OWENSVILLE

Owensville began as a single sod and stone dwelling built in 1861 by A. Van Fleet, a member of a cattle drive that entered the Owens Valley in search of new grazing land. A severe drought had withered the pasture lands of California’s Central Valley, and stockmen were desperate to find feed for their sheep and cattle. They discovered grazing land in the Owens Valley, and later the land’s ability to produce crops, leading to the agrarian society in Owens River Valley.

But it was mining speculation in the White Mountains to the east, followed by the rush of miners that spurred the growth of Owensville. By late 1862 this town was on its way to becoming the largest settlement in the northern Owens Valley. Its growth was told in a letter sent from Owensville to the San Francisco newspaper Alta. One family wrote, “I have just arrived with a party of 56 men, one family, 82 yoke of oxen and saddle horses innumerable.”

Named by the miners, Owensville was growing faster than the Valley’s ability to provide goods and services. Provisions had to be shipped in from the north and south; shortages were inevitable. At one point an Owensville merchant turned down twenty dollars for a sack of flour saying he needed it to feed his family. Regardless, this river town was a bustling community and many prominent people of the time lived there, even though living conditions were very modest. In May 1864 the first recorded social event in the northern Owens Valley took place: a dance in a ten by twelve foot room of an adobe house.

Modest or not, demand for real estate skyrocketed with corner lots valued as much as $1,500. But the promise of mineral riches in the White Mountains never materialized and Owensville declined rapidly, and by 1871 the last resident departed.

Owensville was dismantled; its lumber piled on barges and floated down the Owens River to be used in settlements to the south. Timber was at a premium in the Owens Valley so when buildings were abandoned, the wood was reused.

Around the time of early Owensville, excitement was growing in the central Owens Valley where expectations were running high for mineral riches, and  where events there eventually lead to the birth of a new county.

where events there eventually lead to the birth of a new county.

In the early 1860s Inyo County didn’t exist. The County of Mono covered a big chunk of the Valley. The central Owens Valley was governed by Tulare County whose boundary reached from the western side of the Sierra Nevada clear to the California/Nevada border. Traveling to its county seat of Visalia, in California’s Central Valley, was a long and arduous journey. In terms of governance, and for all practical  purposes, Owens Valley was on its own.

purposes, Owens Valley was on its own.

Early prospectors and residents were in need of some form of self-government, so miners created “mining districts.” They drew up rules and procedures for establishing mining claims, and for resolving disputes. Even after Inyo County was formed in 1866, miners continued to rely on these mining districts as county government was slow to develop.

The first mining district was formed in April 1860 and named after Colonel H.P. Russ of the San Francisco-based New World Mining and Exploration Company. The Russ Mining District in 1864 was absorbed by the vast Inyo District which covered nearly every mine surrounding the Owens Valley, including the mines that spawned the next river towns.

SAN CARLOS AND BEND CITY

In the early 1860s, according to the newspaper Visalia Delta, up to 100 men were prospecting in the central and southern Inyo Mountains east of the Owens Valley. Precious metals were soon discovered, and the San Francisco publication Mining and Scientific Press declared gold and silver in these areas would deliver “riches beyond computation.” Mining at Cerro Gordo quickly lived up to its hype. But other mines, east of present day Independence, were slower to evolve.

The arrival of miners, ranchers, and farmers inevitably overwhelmed the original inhabitants of the Owens Valley and the Native Americans fought to protect their food sources and ways of life. To quell the inevitable conflicts military troops were sent to the region, and Fort Independence was established. The presence of troops created a tense stalemate, and the fear of violence was ever present in the life of the River Towns.

Around 1862, a soldier strolled along the foothills near Mazourka Canyon east of Independence and discovered gold. The San Carlos Mining and Exploration Company was quickly formed. A stamp mill and mining camp was established on the eastern bank of the Owens River; in 1862 San Carlos was born.

Around 1862, a soldier strolled along the foothills near Mazourka Canyon east of Independence and discovered gold. The San Carlos Mining and Exploration Company was quickly formed. A stamp mill and mining camp was established on the eastern bank of the Owens River; in 1862 San Carlos was born.

In the September 4, 1863 edition San Francisco newspaper Alta, in a regular feature called “Letters from San Carlos,” came word that the river town was “progressing rapidly” with a population of 200 people. There were numerous stores, butcher shops, assay and express offices, a saloon, and mechanics of all kinds. However, another town would soon surpass it.

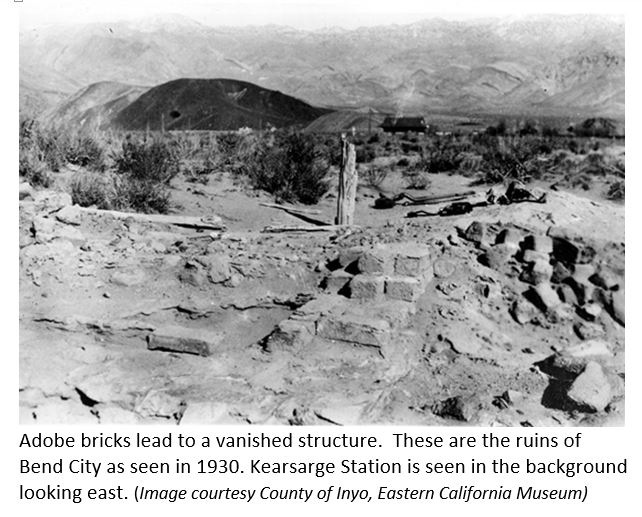

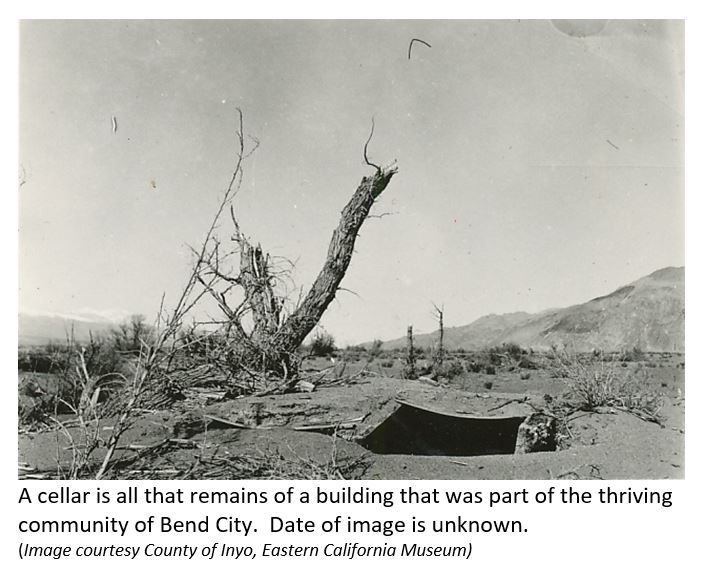

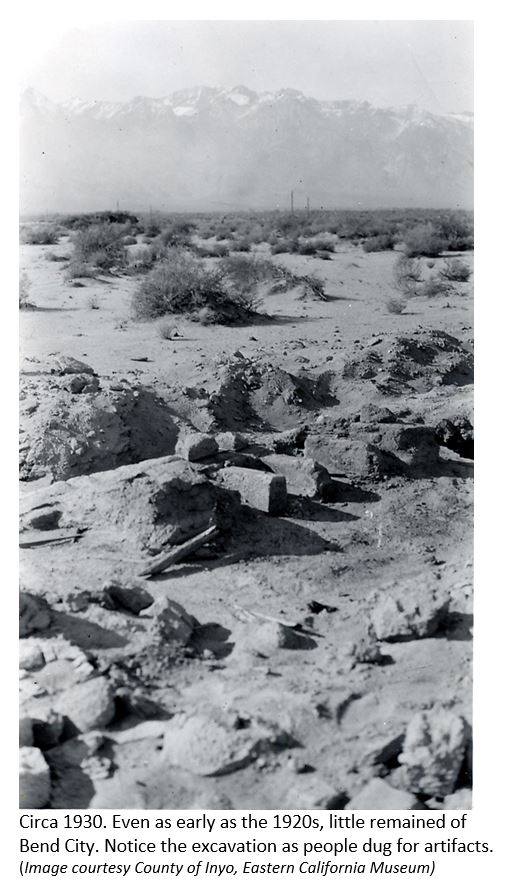

Three miles downstream, on a great bend in the Owens River, in late 1863, Bend City was born.

Bend City grew to over 30 adobe houses with some accounts claiming over 60, plus five mercantile houses, two eating establishments, two hotels, library, stock exchange, blacksmith shops, a saddle and harness maker, tailor shop, and laundry. A rivalry began.

With no roads or bridges, San Carlos ferried men and horses across the Owens River using a crude raft pulled back and forth by a rawhide rope. Not to be outdone, Bend City built their own ferry, but they charged a fee. Bend “Cityite’s” had little money and little tolerance for a toll, so the town decided to build the Owens Valley’s first bridge. That started an intra-town rivalry with “uptowners” on the north end of Bend City wanting the bridge there, and the “downtowners” wanting it on the southern end. The fight was settled by a vote; the “downtowners” won, and the $2,000 Bridge was built. But ironically, and for unknown reasons, the “uptowners” ended up paying for most of it.

Supplies for the river towns initially came from freight wagons traveling up though the valley on their way to Aurora and other mining towns that were over one hundred miles to the north. But as settlers began pouring into the Valley, local farming and ranching filled their need with corn, potatoes, cabbage, and other vegetable’s along with fresh meat including fish, deer, and cattle.

Bend City citizens felt they were destined to become the new western metropolis so they began the process of creating a new county. Working with regional state representatives, they proposed carving out portions of Tulare and Mono counties. The new county would be called Coso County and Bend City would be the county seat.

In 1864, legislation was passed to create the State’s newest county. Everything was going as planned, all they needed was voter approval, which was successful. Nothing could stop them now...except for the fact they held the election on the wrong day. It nullified the entire legislation and the law was rewritten

But rather than being called Coso, the new county was named Inyo. And unfortunately for Bend City, the honor of the new county seat was given to Independence. It was the beginning of the end for the local river towns. The mines were inefficiently operated and became cost prohibitive. San Carlos died, and Bend City was fading as its residents slowly relocate to Independence.

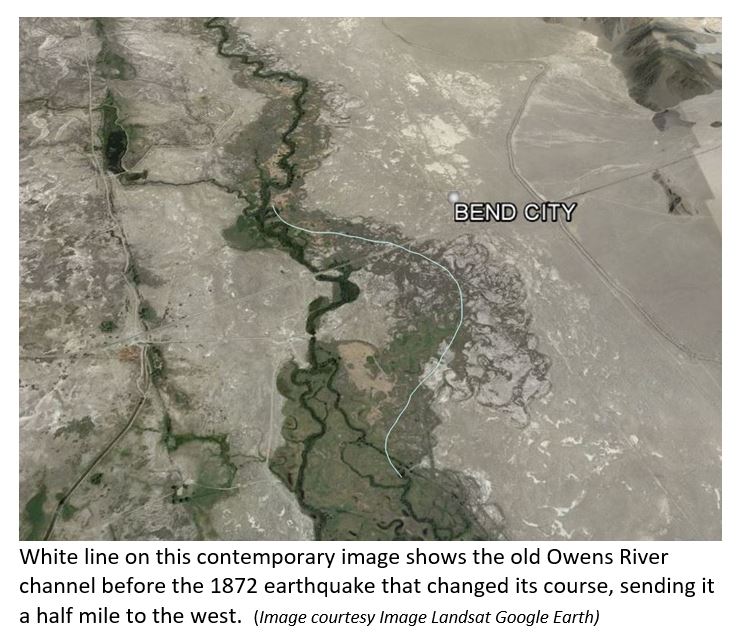

The final blow came in March of 1872 when the great Owens Valley earthquake hit. It was so powerful it changed the course of the Owens River away from Bend City. The Valley’s first major bridge now spanned a dry channel.

The river towns of the Owens Valley were iconic settlements that reflected the boom and bust of mining. But they supported more than that, they helped initiate farming and ranching. The Owens Valley River Towns marked the threshold of an emerging agrarian society that would continue for the next 50 years, but that’s another story.

Copyright © 2018 Ted Williams, All Rights Reserved